Can you change the properties of fascia or ‘break up’ fascial adhesions?

WTF is ‘Fascial Stretch Therapy’?

And are you really creating change by foam rolling your ITB – a fascial band?

What is Fascia:

A band or sheath of fibrous connective tissue which permeates like a 3D Matrix throughout the body, encasing muscle, bones and organs. Fascia Research Congress 2007 explains that fascia is known to play an important role in transmitting mechanical forces between the aforementioned structures.

What Else Does Fascia Do?

Healthy, relaxed fascia is a series of wavy connective tissues and is largely made of collagen fibers which have viscoelastic properties. While purely elastic materials strain when stretched and immediately return to their original state once the stress is removed just like an elastic band, viscoelastic properties differ. Viscoelastic properties exhibit time-dependent strain, meaning they will tighten when stressed, until a point in time where they can no longer handle the forces and break. Despite fascia being viscoelastic, it isn’t as elastic as you might think and although fascia is partly collagenous, it isn’t dense in collagen and this is useful to transmit force.

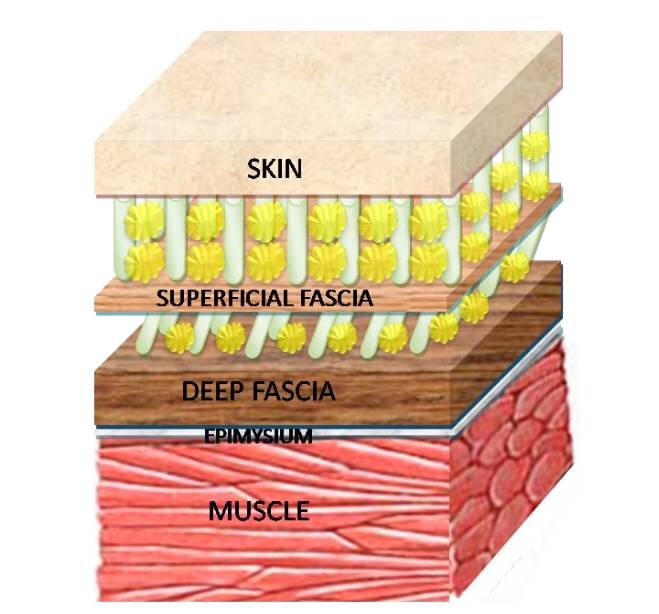

Fascia Has 3 Layers, Each With Unique Properties

1. Superficial

Directly under the skin

2. Deep

Surrounding bones, muscles, nerves and blood vessels (can contain nerve endings which are sensory neurons/ mechanoreceptors). Deep fascia also blends into the epimysium (a dense sheath of connective tissue surrounding muscle). While the epimysium encases muscle and protects it from friction with other structures, deep fascia can also permeate the muscle.

Ruffini endings: detect tension and deep pressure in fascia

Pacinian corpuscles: detect vibrations, touch and heat in fascia (known to be sensitive to painful stimuli)

3. Visceral (not shown)

Pertaining to internal organs

For the purposes of movement and training, we will discuss only the deep fascia.

The 3 Functions Of Fascia

1. Acts Like Tendons By Transmitting Forces (Stecco 2016)

The fascial network is intimately bound to muscle and therefore we must understand that force transmission cannot be isolated to just fascia (Passerieux et al., 2007).

Myofascial force transmission occurs as a result of mechanical tension generated by muscle contraction (Huijing, 2003). This happens either:

1. Intermuscularly

Between 2 adjacent and synergistic muscles – muscles which perform the same or similar movements)

2. Extramuscularly

Between a muscle and something else, such as blood vessels or nerves. Forces exerted this way may play a role in stabilising joints

This occurs through the principle of tensegrity which, in the body, explains how all human tissues (bones, muscles and connective tissue) form part of a continuous fascial network. Therefore, structures in the body can be tensioned or compressed and these forces are distributed throughout the network as it functions as one unit.

E.g. Pulling on a spider’s web affects the entire web, not just the area of tension.

However, this is conditional based on the compliance of the connection, (i.e. the lower the stiffness) the harder it is for force to be transmitted. Tissue stiffness needs to be high enough for force to be transmitted. So, the “tighter” the fascia, the quicker force is transmitted to other areas.

Imagine a rope attached to a sled. If the rope is laying limp on the floor, you have to pull the rope until it is taught for the sled to move, the same happens with fascia acting on the body. The more a structure has to move before the fascia becomes taught, the smaller the impact the fascia will have on the connected structures.

Keep in mind that fascia is never completely “loose” like a limp rope on the floor, as all living things have and need tone, and so there is always inherent tension within any tensegrity system.

2. Fascia Produces Tension To Resist Force

Under stretch, fascia is exceptionally strong when it comes to resisting tension as it creates strain (Wang, 2009). Think about a slackline. The more stretched it becomes, the more tension it creates and the firmer it is in structure. This is how fascia can generate muscular activation.

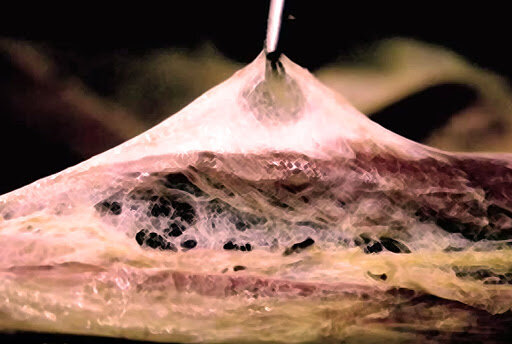

3. Fascia Reduces Friction

By creating a gliding and sliding mechanism to allow as much force as possible to be transferred from one muscle to another or an external load (i.e. when lifting) and is vital in avoiding force lost due to friction.

Can You Stretch Fascia?

There are active contractile elements in fascia (Schleip et al., 2005).

Thus, fascia does have some stretching capacity. It has to, so it can allow for normal blood flow, nerve conduction and swelling of underlying structures (like muscle swelling we see immediately following exercise).

If Fascia Can Stretch… Can It Also Become Stiff?

We know fascia can become stiff as shown with neuromuscular conditions such as spastic palsy as well as autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

What Happens To Fascia When We Get Injured?

However localised fascial stiffness can also be found in areas of present or past inflammation and trauma. In these locations we see dense connective tissue rich with myofibroblasts (the creation of new cells). Fascia loses its pliability which leads to tension and restricts movement, reduces blood flow and increases pain sensitivity of the underlying tissues (think muscles and organs) (Gatt et al., 2019).

Fascial Stiffening Due To Injury Has Been Shown In:

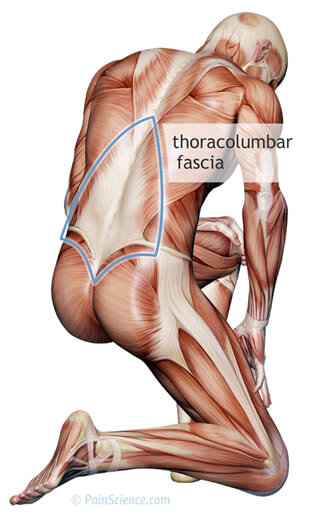

- Thoracolumbar Fascia

- ~25 % thicker in men with chronic back pain (Langevin, 2011)

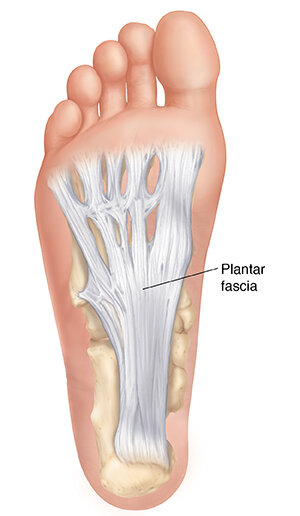

- Plantarfascia

- Thickness in symptomatic patients was significantly greater on Ultrasound than that in non-symptomatic patients (Fabrikant & Park., 2011)

Fascial Stiffening Due To Injury Has Been Shown In:

- Thoracolumbar Fascia

- ~25 % thicker in men with chronic back pain (Langevin, 2011)

- Plantarfascia

- Thickness in symptomatic patients was significantly greater on Ultrasound than that in non-symptomatic patients (Fabrikant & Park., 2011)

Inversely, in the same study fascial thickness diminishes with what they deemed successful treatment and in a second study was even shown to decrease further after one bout of running versus walking (Wearing et al., 2007).

Interestingly, there is conflicting evidence as to whether this thickened fascial tissue is also a potential factor for pain. Tissue stiffness is not related to pain experience (Lederer et al., 2019). While we know that pain is extremely complex and multifaceted, there does seem to be a correlation between inflammation and CNS sensitivity of these pain receptors

Additionally, those experiencing pain were found to have a reduction in sliding capacity (and thus more friction was present) during passive flexion of this fascial structure in relation to the underlying musculature.

E.g. Pulling on a spider’s web affects the entire web, not just the area of tension.

However, this is conditional based on the compliance of the connection, (i.e. the lower the stiffness) the harder it is for force to be transmitted. Tissue stiffness needs to be high enough for force to be transmitted. So, the “tighter” the fascia, the quicker force is transmitted to other areas.

Imagine a rope attached to a sled. If the rope is laying limp on the floor, you have to pull the rope until it is taught for the sled to move, the same happens with fascia acting on the body. The more a structure has to move before the fascia becomes taught, the smaller the impact the fascia will have on the connected structures.

Keep in mind that fascia is never completely “loose” like a limp rope on the floor, as all living things have and need tone, and so there is always inherent tension within any tensegrity system.

2. Fascia Produces Tension To Resist Force

Under stretch, fascia is exceptionally strong when it comes to resisting tension as it creates strain (Wang, 2009). Think about a slackline. The more stretched it becomes, the more tension it creates and the firmer it is in structure. This is how fascia can generate muscular activation.

3. Fascia Reduces Friction

By creating a gliding and sliding mechanism to allow as much force as possible to be transferred from one muscle to another or an external load (i.e. when lifting) and is vital in avoiding force lost due to friction.

Can You Stretch Fascia?

There are active contractile elements in fascia (Schleip et al., 2005).

Thus, fascia does have some stretching capacity. It has to, so it can allow for normal blood flow, nerve conduction and swelling of underlying structures (like muscle swelling we see immediately following exercise).

If Fascia Can Stretch… Can It Also Become Stiff?

We know fascia can become stiff as shown with neuromuscular conditions such as spastic palsy as well as autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

What Happens To Fascia When We Get Injured?

However localised fascial stiffness can also be found in areas of present or past inflammation and trauma. In these locations we see dense connective tissue rich with myofibroblasts (the creation of new cells). Fascia loses its pliability which leads to tension and restricts movement, reduces blood flow and increases pain sensitivity of the underlying tissues (think muscles and organs) (Gatt et al., 2019).

Fascial Stiffening Due To Injury Has Been Shown In:

- Thoracolumbar Fascia

- ~25 % thicker in men with chronic back pain (Langevin, 2011)

- Plantarfascia

- Thickness in symptomatic patients was significantly greater on Ultrasound than that in non-symptomatic patients (Fabrikant & Park., 2011)

Fascial Stiffening Due To Injury Has Been Shown In:

- Thoracolumbar Fascia

- ~25 % thicker in men with chronic back pain (Langevin, 2011)

- Plantarfascia

- Thickness in symptomatic patients was significantly greater on Ultrasound than that in non-symptomatic patients (Fabrikant & Park., 2011)

Inversely, in the same study fascial thickness diminishes with what they deemed successful treatment and in a second study was even shown to decrease further after one bout of running versus walking (Wearing et al., 2007).

Interestingly, there is conflicting evidence as to whether this thickened fascial tissue is also a potential factor for pain. Tissue stiffness is not related to pain experience (Lederer et al., 2019). While we know that pain is extremely complex and multifaceted, there does seem to be a correlation between inflammation and CNS sensitivity of these pain receptors

Additionally, those experiencing pain were found to have a reduction in sliding capacity (and thus more friction was present) during passive flexion of this fascial structure in relation to the underlying musculature.

Here’s What We Now Know About Fascia?

Fascia’s main roles are to:

a) Transmit forces

b) Produce tension to resist force

c) Reduce friction

Fascia Can Also:

- Stretch (to a degree)

- Be a source that receives sensory input

- Thicken due to injury and restrict range of motion, while it also may have the potential to thin as a result of exercise and movement

With all this being said, there are still a few very key unanswered questions which I’d like to see addressed in future literature:

1. Can you ever truly stretch fascia in isolation (without affecting other structures)?

2. How much stretch does fascia have in a living human before it breaks?

3. Can fascial thickness caused by injury decrease with movement over time?

Questions? Comments? Thoughts? I’d love to hear from you. Add your thoughts below!

#MOVESWIFTLY